New content and updates over at @jeremyzine

May 2024 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 -

Join 378 other subscribers

The Jedi look of the Star Wars universe is known even to those who have never seen a film. Ascetic with strong hints of Asia (and notions of Africa), spiritual, elegant, humble and at the same time grand, it is an aptly and often used reference in contemporary dress. Whether it’s cosplay at a sci-fi convention or a Rick Owens runway, it’s not impossible to find a real life context.

Nehera Fall/Winter 2015

Authored by John Mollo for the first Star Wars film in 1977 (Mollo would go on to costume Alien and Gandhi), the look elucidates George Lucas’s spiritually guided, space-dwelling wizard-knights from a time long long ago in a galaxy far far away. To bring them to life Mollo created a unique language of dress that has since become a part of popular culture and consequently fashion. Long flowing fabrics purposely but casually draped. Tonal palettes made up of white, cream, beige, nut and earth. Shawl and wrapped collars. Wrapped everything. A strong sense of calm as well as power. A look to the future? A memory of the past? You can begin to see what makes it so appealing.

One of the most enjoyable and important interpretations of the Jedi look, and what is possibly one of the best fashion moments in sci-fi history, is actually in the newest Star Wars installment, Episode VII: The Force Awakens.

Marni Spring/Summer 2015

The film was costumed by the legendary designer Michael Kaplan, revered for his work on Blade Runner. Kaplan also worked with Star Wars director J.J. Abrams prior on his well-received Star Trek reboot. The new Star Wars costumes are entirely based on Mollo’s precedent however Kaplan is charged with the hyper-complex task of negotiating late ‘70s retro-futurism with the look of today. The costumes are worthy of his reputation except in seldom moments where the designs are not as convincingly carried by the actors. In these minor but noticeable breaks in suspension of disbelief it was difficult to know whether it was the costume or the limits of the actor.

It’s not significant enough to dwell on. Ultimately, Episode VII is easily the second best Star Wars movie ever made (possibly the best). The film is an amazing experience that Kaplan’s skill and creative invention worked to uplift.

Lemaire Fall/Winter 2015

And there is one special moment where the story, character, and costume come together with such utterly thrilling results. In a gesture, a glance, in the glint of the eye, in the worn but robust fibers of humbly woven cloth comes a fashion moment few films contain. It stirs you. It shakes you. You are truly moved. The depth and significance of this moment is as much about the clothing as it is Abram’s storytelling or the talent of the actor who pulled it off. It’s possible you will begin to see things differently. It may change your eye.

But it’s impossible to tell you what that moment is without spoiling it for those who have not yet seen the film. Those who have know exactly the moment I mean. Those who still need to go, I can tell you only this: the timing is perfect.

Courrèges by Jean Charles de Castelbajac, 1993

The called him “The New Hermes,” a reference to his uncanny abilities in leather and exquisite construction. But he was maybe a bit too irreverent, too deliberately immature, for that moniker to stick.

Jean Charles de Castelbajac emerged in Paris in the late ’70s alongside an angst-ridden generation of designers who were ready to redefine the future of fashion with everything pret-a-porter could muster. Kenzo, Montana, Mugler, Rykiel and, eventually, Gaultier; while they all entertained a certain amount of humor that was, at that time, unbecoming of French fashion, it was and his particular joie de vivre that was especially infectious. Becoming a poster boy for inventive French fashion in ’80s, it was in the early the ’90s that he caught the eye of Space Age legend André Courrèges who appointed the Castelbajac to carry on his legacy.

The collaboration was short-lived, lasting only two seasons. But it highlights a rather under discussed facet of the Courrèges mythology. In the wake of the Space Age Courrèges shifted gears. His interest in futurism and space-inspired clothing was never purely formal, for him it was a means to optimism, to progress and, most importantly, to a better way of life. As the ’70s came around he applied his futurist ethos to sportswear, presaging the athleisure trend fashion is currently undergoing. It suited his specific philosophy on life and living: active, healthy, celebratory and fun. FYI, when Christophe Lemaire did Lacoste, it was this idea of sport and that guided his direction for the brand.

For Castelbajac, in the midst of minimalism in the early ’90s, it was an interesting exercise that gave way to inventive, witty, and ebullient clothing. And it’s currently of note not because of its relationship to the recent revival of the house of Courrèges by designers Sébastien Meyer and Arnaud Vaillant, but actually because of the collection shown the just the day before by Simon Porte Jacquemus.

In recent seasons the punchy (not to mention extremely crushable) young designer has become Paris’s new enfant terrible. Unapologetically French, playfully precocious, and fearless in his use of abstracted form, he favors the same bright gestures and visual hyperbole that was a signature of Castelbajac while his brand philosophy, which espouses confident living and a childlike openness to new experiences, is not dissimilar from Courrèges. In many ways he has picked up were Castelbajac left off in 1994.

The collection he showed for Spring Spring/Summer 2016 was as tender as it was violent, a youthful rebellion against the tyranny of mature appropriateness. It seemed to outline esoteric attitudes of dress for pretty young things, simultaneously sexualizing and dismissing their bodies. It was pop and perky, seductive and quirky, and while it only looked on to the future, it did make one think of the past: a time when fashion could inspire emotion, when clothes could make you feel something beyond consumerist pangs of desire. It was a collection of the future, surely, but it managed to take you back. Back to a very a good place.

Posted in Collections, Review

Tagged 1993, Courrèges, Jacquemus, Jean-Charles de Castelbajac, Spring Summer 2016

DKNY, 1992

The brand was founded at a time when fashion itself was a bit more more matter-of-fact. The consumer was uninitiated, ignorant of the nuances of a neurotic industry, free from of the black hole of self-awareness and hum of ennui that contemporary fashion now seems to be desperately trying to escape. In the early ’90s all you needed was a beautiful cable sweater with modern proportions and equally well-dressed family and friends to achieve your sartorial ambition. It was simpler times.

DKNY is not a list of codes like fake pearls and cap toe shoes but rather an attitude about modern living, specifically a modern urban living. It could wander into the historicist tangents Ralph Lauren often gets lost in or it could go as stark (but not as bleak) as Calvin Klein. Either directions worked provided they serviced a certain understanding of city life.

Throughout the ’90s DKNY dominated the market appealing to a younger, urban-oriented consumer who, though not shopping designer collections, could afford to spend a bit more to buy a nicely done jacket, in black crepe for the town, in tweed for the country. Or perhaps pick up an inventively cut but wholly appropriate black dress, prime for a gallery opening or a good day at the office. Throughout the ‘90s, not unlike the television show Friends which seemed to validate the urban lifestyle DKNY sold, it reigned supreme.

In the early 2000s things took a turn for the worse. Perhaps, as minimalism started to go out of fashion, they had diluted the brand beyond what its conceptual and material integrity could uphold (shitty licensing is a bitch). Maybe it was Sex in The City garishness taking over the fantasies of impressionable young women. Maybe it was Zara eating their lunch. And you can never underestimate the wildly destructive combo of lazy creative management and conservative business. It was most likely a combination of all these things. By 2007 the brand was on the express track towards irrelevance. It still made great product, but it was falling into the garmento traps that have often spelled doom for many American fashion brands. DKNY had become dowdy and mind-numbingly bland, a slave to its unflattering licensees and to a customer who didn’t know enough to know to move on. Rumors of LVMH’s imminent shedding of the dead weight ran rampant and each season anticipated the dread announcement that the brand would finally be sold off to a PVH or Kellwood and take its place in fashion hell.

But then around 2011 there was a change. A good one. While the marketing was still questionable (neon lights 4eva) the collections improved and even managed to surprise in a few instances.

A collaboration with Opening Ceremony was the tipping point. Acknowledging their ’90s heritage without shame revealed what their old values meant to a new generation. Spurred by the endorsement of vintage king supreme Brian Procell and aided by OC’s Jacky Tang’s good judgment, DKNY looked on course for a proper revival. It was a move in the right direction when they cast Juliana Huxtable to walk in their fall 2013 fashion show, even if the fashion message missed the mark. It showed that not only were they were capable of taking risks but were able to choose the right ones to take. Enter Maxwell Osborne and Dao-Yi Chow.

Osborne and Chow are the founders of Public School and the new creative directors of DKNY (replacing the brand’s founding designer and industry legend Jane Chung). It was a doubt-inducing decision. Though known for their urban sensibilities, the designers don’t always have enough good ideas for one collection a season let alone two. Their first effort for DKNY, shown just this past NYFW, sadly confirmed those doubts. They opted for a strict, minimal interpretation of the brand, a shortsighted look back at its heyday during the late ‘90s. It read more like a poor man’s Jil Sander (Navy). They misused and abused white shirting, bullying it into forms and styles no woman wants to wear. They attached pleated flaps, in striped suiting (a nod to the schoolgirl archetype which is in fact a pillar of the house), aimlessly to almost anything they could without any consideration of what they might actually accomplish (often nothing). There were oversized jackets which weren’t new, wrapped skirts which didn’t work, and archival photo prints on mesh that literally lacerated the brand’s history. It was all styled to be mannish and was set against a soundtrack that echoed words about men and victory and womanhood. It was not their victory to be had.

No, it was not a good effort. And it doesn’t mean Osborne and Chow won’t manage one next time, but it would serve them to realize that DKNY is not about any obvious effort or strenuous concept, or hackneyed cliché of a strong, modern, independent woman (blah blah blah). It’s about ease and sensuality, a potent honesty about life in New York City today. If they can manage just an ounce of verisimilitude, along with a relevant opinion about city dressing, they might get that much closer to the DKNY of yesteryear that was once so incredibly important.

Tagged Cable Sweaters, Dao-Yi Chow, DKNY, Jane Chung, Maxwell Osborne, Public School

Agnes Martin, 1965

Adam Lippes knows luxury. He learned it as the right hand to the late Oscar de la Renta and it is literally threaded throughout the hand-sewn finishings of his demi-couture clothes (which he is obliged to sell at ready-to-wear prices). But if in the past his collections have veered towards precious, or even haughty, Lippes has remedied that this season with an appeasement to womanly comforts that are as liberating as they are indulgent. It is the justly outcome when you take on sultry songstress Nina Simone and austere artist Agnes Martin as inspiration. Seemingly disparate, the two women share an utterly modern point-of-view and a resilient but quiet strength. Lippes has harnessed these qualities and has transmuted then into the rarest form of luxury in our modern day: humility.

It was the the righteous contradiction of humble luxury that erupted into one of Lippes’s best collections ever. Taking cues from the the monastic simplicity of Martin’s artist dress as well as Simone’s own sumptuous, though inconspicuously so, style, he presented a collection of quiet clothes that sang. They were quiet in their shapes: easy and unassuming, shapes that a woman could easily slip on, flatter her, and give her no further fuss as she goes about her day. And they sang in the details: the hand-stitched silk grossgrain placket on the back of a cotton tunic, stitched just so as to ensure the neck lays perfectly. They sang in the the multitudes of finely pleated cotton, cut in a peasant shape, as luxurious as any pastoral costume worn by Marie Antoinette on her faux farm. The height of modesty came in a bleached denim apron dress with an inventive and aesthetically delightful tie in the back. Its hem was bound, turned up and blind stitched by hand. It was nearly sinful in its decadent ease.

This season spoke to an emerging feminist philosophy which Lippes has made clear in his shoes for the collection. Flat sandals, designed for Manolo Blahnik, were ornamented with ruffled flounce and marked a new direction for his footwear and a significant shift in his design methodology “If you can’t wear it with flats,” Lippes stubbornly and endearingly declared, “we aren’t making it.”

But a Lippes collection is never whole without the flexing of his couture muscle. A jumpsuit, overlaid with a knotted silk cording came from a reference to Simone’s penchant for macramé. Uniform in appearance, not one of its perfectly formed squares are alike; each are subtlety altered in size and angle, through a process painstakingly executed by skilled hands, as to move flawlessly over the curves of a woman’s body. The reward of such intricate and time-consuming effort, not to mention cost, is perfection. The notes for the collection featured a quote by Agnes Martin: “Simplicity is never simple. It’s the hardest thing to achieve” and Lippes proved he knows this better than anyone else.

Nina Simone, 1965

Posted in NYC Fashion Week, Review

Tagged Adam Lippes, Agnes Martin, Humble Luxury, Nina Simine, NYFW, Spring Summer 2016

You can’t help but think of a young Lauren Bacall clad in Carolyn Schnurer, captured by Louise Dahl-Wolfe, lounging in the pages of Harper’s Bazaar circa 1946. It’s not a bad thought.

Theirs is a vintage-oriented gaze that curiously looks back to a time of absolute modernism. Since launching Trademark in 2013, sisters Luisa and Pookie Burch have championed a lost American aesthetic, reprising the pragmatic sensibilities and precocious wit of the ‘40s era designers whom they appear to be enamored with. There’s Carolyn, of course, but also Bonnie Cashin, Tom Brigance, Clarepotter and most certainly Claire McCardell.

It was a time when American optimism saw its most ingenious designers looking to the realities of everyday life, as well the everyday realities found in life around the globe. They used this keen vantage to enhance their own foundations in sportswear and turn the practical into the remarkable and their American allure of ease outstripped any tediously constructed thing the French could manage.

The effect the sisters have today is not dissimilar. Amidst the whir of fashion brands that currently occupy too much space on the market, Trademark’s wholly realized and immaculately detailed vision of sophisticated simplicity resonates. Strongly.

It’s not design for the sake of a trend, or worse, entertainment, or worse still: not-knowing-better. It’s design intended to charm the wearer, to give her the humble satisfaction that only a wrapped sash of an A-line textured cotton skirt can bestow. It’s the indulgently naïve placement of pom-poms along a superbly considered knit sweater, it’s a trouser that whips about your shins as you saunter. It’s the confidence of sculpted metal adorning the ear.

The clothes, simultaneously proper and primal, evoke a sense of longing. Perhaps it is Luisa and Pookie’s own thirst for eras past. Perhaps it’s the romance of a triumphant and intelligent modern America. You can’t help but ponder what appeasements to contemporary life they might offer and what hidden away glamour they may unlock. These clothes tease and taunt you with a world long past and, in their breathtakingly casual splendor, what might be today.

Posted in Collections, Review

Tagged Carolyn Schnurer', Lauren Bacall, Louisa Burch, NYFW, Pookie Burch, Spring Summer 2016, Trademark

“For me, luxury is a sensibility, an approach to life. It’s not about the season’s newest anything. It’s about personal style and creating an environment of comfort and ease.”

-RALPH LAUREN

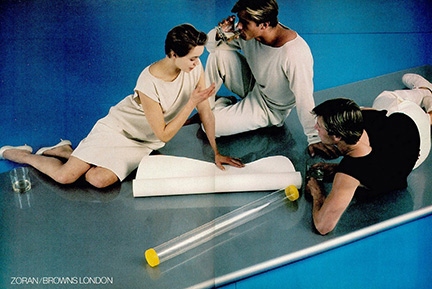

“Wearing sneakers and no socks, white pants and a long beige cashmere and silk sweater from Zoran’s warm weather collection, Candice Bergen watched the proceedings perched on a platform along with retailers and members of the fashion press.

Zoran has expanded his collection of men’s styles, which are no more complicated than his women’s clothes. It is a natural development since men have been buying his women’s sweatshirts, Dawn Mello of Bergdorf-Goodman said.

With no collars, pockets hidden in side seams and a total absence of pattern, the clothes have all their style built into the cut. They are made in one size only, and manage to fit most people.”

-BERNADINE MORRIS for the NYT, 1982

Posted in Archival Article, Vintage Campaign

Tagged 1982, Bernadine Morris, Candice Bergen, Zoran

Tickets are available here

Polish born, American raised, Italian and French trained (she served as studio director for Sonia Rykiel before going out on her own) Mona Kowalska is the founder and designer of sixteen-year-old cult label and store A Détacher. The name means “to detach” in French but it’s a misnomer, Kowalska’s clothes, designed consummately from her own personal affections, are objects of desire and induce a high level of attachment for those who appreciate and wear them. Her collections, a mix of sly engineering, sympathetic notions of womanhood, and a vivid wit are a rare delight in a superfluous sea of fashions. Independent and delicate, nuanced but approachable, the clothes cut through the smoke and mirrors fashion often uses to drum up false appeal and get to the matter at hand: to offer something special yet wholly believable for a woman to wear. Designing with integrity, drafting the patterns herself (no mean feat, Kowalska’s shapes wonder as much as they flatter the female form) and made with the finest fabrics, each garment is considered from the inside out. She is the very ideal of a modern clothing designer, her clothes representing not just a style or a look but an attitude, a world, one that she offers without hesitation and through her collections and in her store she serves in spades.

tickets are available here.

Posted in Event

Tagged a detacher, Designing Women, Jeremy Lewis, Mona Kowalska, Museum of Arts and Design