DKNY, 1992

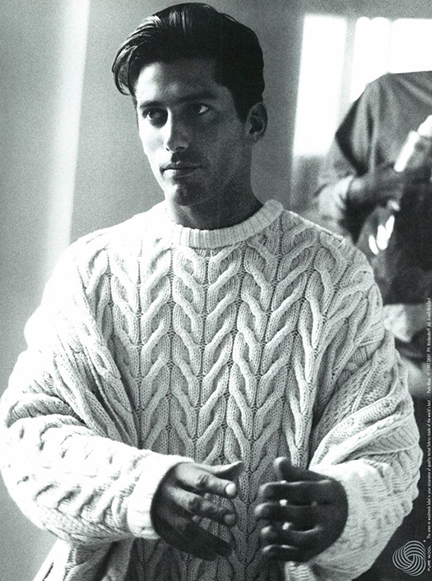

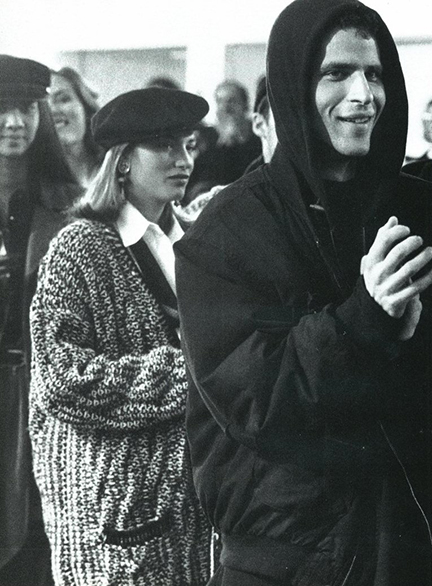

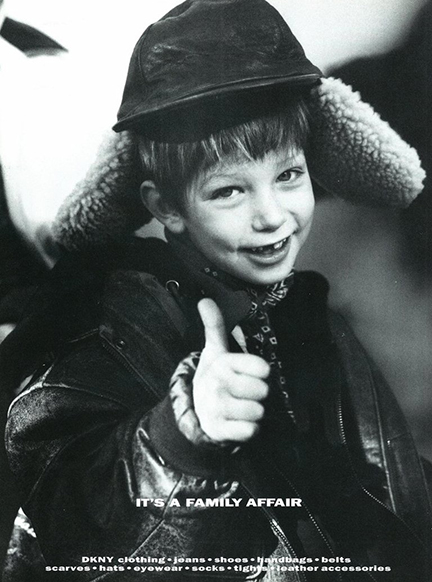

The brand was founded at a time when fashion itself was a bit more more matter-of-fact. The consumer was uninitiated, ignorant of the nuances of a neurotic industry, free from of the black hole of self-awareness and hum of ennui that contemporary fashion now seems to be desperately trying to escape. In the early ’90s all you needed was a beautiful cable sweater with modern proportions and equally well-dressed family and friends to achieve your sartorial ambition. It was simpler times.

DKNY is not a list of codes like fake pearls and cap toe shoes but rather an attitude about modern living, specifically a modern urban living. It could wander into the historicist tangents Ralph Lauren often gets lost in or it could go as stark (but not as bleak) as Calvin Klein. Either directions worked provided they serviced a certain understanding of city life.

Throughout the ’90s DKNY dominated the market appealing to a younger, urban-oriented consumer who, though not shopping designer collections, could afford to spend a bit more to buy a nicely done jacket, in black crepe for the town, in tweed for the country. Or perhaps pick up an inventively cut but wholly appropriate black dress, prime for a gallery opening or a good day at the office. Throughout the ‘90s, not unlike the television show Friends which seemed to validate the urban lifestyle DKNY sold, it reigned supreme.

In the early 2000s things took a turn for the worse. Perhaps, as minimalism started to go out of fashion, they had diluted the brand beyond what its conceptual and material integrity could uphold (shitty licensing is a bitch). Maybe it was Sex in The City garishness taking over the fantasies of impressionable young women. Maybe it was Zara eating their lunch. And you can never underestimate the wildly destructive combo of lazy creative management and conservative business. It was most likely a combination of all these things. By 2007 the brand was on the express track towards irrelevance. It still made great product, but it was falling into the garmento traps that have often spelled doom for many American fashion brands. DKNY had become dowdy and mind-numbingly bland, a slave to its unflattering licensees and to a customer who didn’t know enough to know to move on. Rumors of LVMH’s imminent shedding of the dead weight ran rampant and each season anticipated the dread announcement that the brand would finally be sold off to a PVH or Kellwood and take its place in fashion hell.

But then around 2011 there was a change. A good one. While the marketing was still questionable (neon lights 4eva) the collections improved and even managed to surprise in a few instances.

A collaboration with Opening Ceremony was the tipping point. Acknowledging their ’90s heritage without shame revealed what their old values meant to a new generation. Spurred by the endorsement of vintage king supreme Brian Procell and aided by OC’s Jacky Tang’s good judgment, DKNY looked on course for a proper revival. It was a move in the right direction when they cast Juliana Huxtable to walk in their fall 2013 fashion show, even if the fashion message missed the mark. It showed that not only were they were capable of taking risks but were able to choose the right ones to take. Enter Maxwell Osborne and Dao-Yi Chow.

Osborne and Chow are the founders of Public School and the new creative directors of DKNY (replacing the brand’s founding designer and industry legend Jane Chung). It was a doubt-inducing decision. Though known for their urban sensibilities, the designers don’t always have enough good ideas for one collection a season let alone two. Their first effort for DKNY, shown just this past NYFW, sadly confirmed those doubts. They opted for a strict, minimal interpretation of the brand, a shortsighted look back at its heyday during the late ‘90s. It read more like a poor man’s Jil Sander (Navy). They misused and abused white shirting, bullying it into forms and styles no woman wants to wear. They attached pleated flaps, in striped suiting (a nod to the schoolgirl archetype which is in fact a pillar of the house), aimlessly to almost anything they could without any consideration of what they might actually accomplish (often nothing). There were oversized jackets which weren’t new, wrapped skirts which didn’t work, and archival photo prints on mesh that literally lacerated the brand’s history. It was all styled to be mannish and was set against a soundtrack that echoed words about men and victory and womanhood. It was not their victory to be had.

No, it was not a good effort. And it doesn’t mean Osborne and Chow won’t manage one next time, but it would serve them to realize that DKNY is not about any obvious effort or strenuous concept, or hackneyed cliché of a strong, modern, independent woman (blah blah blah). It’s about ease and sensuality, a potent honesty about life in New York City today. If they can manage just an ounce of verisimilitude, along with a relevant opinion about city dressing, they might get that much closer to the DKNY of yesteryear that was once so incredibly important.

Wonderfully written, thank you! You nailed this….I suspect that Osborne & Chow may regret their decision to abandon Public School….I think they are in over their heads and don’t understand the essence of DKNY nor are they ready to cope w/ the demands of a large scale sportswear company…..I wish them well but this does not bode well for DKNY customers.

Very well said, I remember when I was craving for both Donna Karan and DKNY at my early teen. IMO, I think Rag & Bone would be a better choice for DKNY than PB.